China in Sri Lanka: Trade, Investment, and the Rise of a New Asian Order

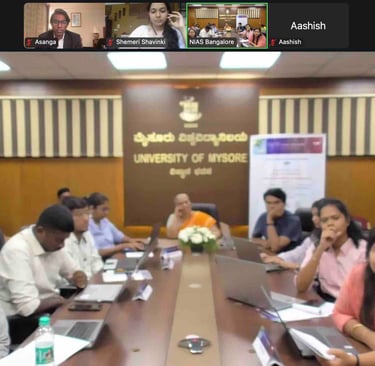

Lecture delivered by Asanga Abeyagoonasekera for the Third CEAP CiSA Workshop on China in South Asia:State of Trade, Investments & Influences Organized by Science, Technology and International Relations (STIR), Programme National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), Bengaluru In collaboration with Department of International Relations, Maharaja’s College University of Mysore (9th May 2025)

NEWS

5/9/20256 min read

It is a privilege to accept the invitation extended by Professor Suba Chandran, whose scholarly contributions to South Asian studies I hold in the highest regard. I also extend my sincere thanks to the National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS) for this opportunity. It is an equal honour to speak with you today on a topic that lies at the intersection of economic ambition, political strategy and regional transformation—China’s in Sri Lanka, and what it reveals about Asia’s shifting power dynamics. In few days I will be in China discussing regional and global geopolitics at a time of conflict, tension and competition.

Let’s begin with a truth that we must all accept: China is no longer an emerging power in Asia—it is a central one. Now I am in Thailand, its trade with China is 120 billion and more, ASEAN’s economic entanglement with China is a strong factor many don’t calculate.

China’s presence is deeply embedded in trade networks, infrastructure corridors, cultural ties, and geopolitical calculations. And perhaps nowhere in South Asia is this more visible than in Sri Lanka. My forthcoming book Winds of Change this August 2025 published by World Scientific, will capture this dynamics in two regions in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Sri Lanka’s ties with China go back more than 2,000 years—rooted in Buddhist diplomacy, maritime trade, and mutual non-interference. However, in the modern era, the relationship gained strategic momentum after 2009. Following the 3 decade civil war, when much of the West distanced itself from Colombo over human rights concerns, China stepped in with a policy of pragmatic engagement. It offered economic assistance without political conditionality, something Sri Lanka welcomed. China stepped into this vacuum, offering billions in infrastructure support through roads, ports, and energy projects. Unlike traditional lenders that come with lengthy conditions or political baggage, China offered quick delivery—some would say too quick—through the Belt and Road Initiative. Today, from the Colombo Port City to the Hambantota Port, from highways to water purification plants, China is physically and economically present across the island. Critics often describe this as a “debt trap,” but that oversimplifies the picture. Much of Sri Lanka’s current economic hardship stems from internal fiscal mismanagement and decisions made by its own leaders—not solely from Chinese loans. In fact, when the West and even India were hesitant to commit, China remained consistent.

Trade numbers also paint a clear picture. China is Sri Lanka’s top trading partners, providing industrial goods and materials. A Free Trade Agreement with China is being discussed, which may tilt the balance even further. Present Government fully support the FTA and issues the following statement “The two sides agreed to work towards the early conclusion of a comprehensive FTA in one package in line with the principles of equality, mutual benefit, and win-win outcomes”. China’s investments in Sri Lanka are not just about economics—they’re also about strategic positioning. Located along vital Indian Ocean routes, Sri Lanka’s ports are essential nodes in global trade. And here’s the part that often causes unease in New Delhi—a security concern for future use as military bases.

Yet the narrative that China is building military outposts or encircling India isn’t entirely grounded in fact. There is no evidence of permanent Chinese naval bases in Sri Lanka. Colombo has repeatedly affirmed that it will not allow its territory to be used for any military activity threatening its neighbors. These are commercial investments, not military ones. The moratorium declared on Chinese Research vessels by Colombo was a clear indication of India’s concern of Chinese vessels used for hydrographic mapping Indian Ocean for submarine warfare. These research vessels has no threat according to Chinese and some Sri Lankan analysts, and Moratorium which is now not renewed does not need further renewal as a maritime nation that should welcome all ships from all countries, explained former foreign minister who imposed this moratorium.

But we must not ignore the political dynamics. And here is where India must be more introspective.While India has strong civilizational and cultural ties with Sri Lanka, its modern foreign policy approach has sometimes lacked nuance. I want to highlight a recent example that came up during my discussions in Colombo last week.

Prime Minister Modi’s recent visit to Colombo was framed as a diplomatic success. But it was quickly overshadowed by controversy—specifically around a defence MoU signed between India and Sri Lanka that has not been made public. I personally spoke with journalists, academics, and civil society representatives in Colombo, and there was strong criticism—not of the content of the MoU, but of the secrecy surrounding it. Many asked: Why would the world’s largest democracy engage in secretive diplomacy with its neighbor? The controversy deepened when a Sri Lankan Government spokesperson claimed they needed India’s permission to release the MoU to the public. That’s not how transparency works in democratic systems. And unfortunately, this moment triggered old memories of the 1987 Indo-Lanka Accord—an agreement signed under pressure, without wide public discourse, which led to violent backlash and, ironically, helped launch the current ruling political movement in Sri Lanka.

The political consequences of this recent MoU are already visible. The local elections that followed saw a drop in support for Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD), partly because of frustration over unclear dealings with India and unfulfilled promises at Presidential election. It became a burden for the new leadership—before they even had a chance to govern. India must learn from these patterns. It cannot afford to rely on a handful of officials with outdated or skewed perspectives—especially when those perspectives fail to read the complexities of Sri Lanka’s political landscape. I say this with respect, and I’m not referring to the professionals in South Block, who often understand the stakes very well. But somewhere between the policy and the execution, there is a disconnect. And when you’re dealing with a fragile neighbor navigating post-crisis recovery, that disconnect can be costly.

India should be engaging Sri Lanka not just as a strategic buffer or a zone of influence, but as a partner in regional development. Soft power—education, healthcare, people-to-people ties—must accompany infrastructure diplomacy. India must be more open, more transparent, and more attuned to public sentiment, especially in countries where democratic politics can shift rapidly.

India should be engaging Sri Lanka not just as a strategic buffer or a zone of influence, but as a partner in regional development. Soft power—education, healthcare, people-to-people ties—must accompany infrastructure diplomacy. This brings me to a quote by Joseph Nye, who sadly passed away just a few days ago. I fondly remember this foreign policy giant from my time at the Harvard Kennedy School, where he taught me a few enduring lessons on diplomacy and soft power—a term he himself coined. He once said, “The best propaganda is not propaganda.” What Nye meant was that influence derived from culture, values, and legitimate policy—rather than coercion or secrecy—ultimately wins more trust. India, as a democracy, should embody this in practice.

Meanwhile, China is not waiting. It continues to embed itself in Sri Lanka’s future—offering grants, investments, symbolic gestures, and strong support at international forums such as UNHRC. From Colombo’s perspective, this is a reliable partner, not one that lectures or overreaches. As students, it’s essential to understand that this is not a zero-sum game—this is about building synergetic relationships among South Asian nations. The future of our region doesn’t lie in rivalry, but in integration. Think of it this way: a box and a wheel on their own do little—but when you bring them together, you get a wheelbarrow, something functional and useful. That’s the power of synergy. We need to shift our mindset from competition to cooperation, from isolation to integration. This idea is powerfully advocated by my mentor in Washington, DC, Jerome C. Glenn of the Millennium Project, who constantly reminds us that complex problems in the 21st century require collaborative, not divisive, solutions. In South Asia, our progress depends on this shift—toward partnerships that make us stronger together than apart.

Sri Lanka doesn’t want to choose between India and China—it needs both. And India, if it truly believes in regional leadership, must earn that role—not assume it. Like I have always said clearly in New Delhi, India’s neighbours should say India is great and not India saying India is great. This requires deep strategic thinking, perhaps missing or inadequate.

Asia is changing. Power is diffusing. And the global South is asserting itself with greater clarity. China’s rise is not a theoretical future—it’s happening, with the present irrational US rhetoric and action. The question is: how will India respond? Will it resist, react, or recalibrate? Or allow a new Asian order to rise.

Let me end by saying this: nations don’t trust words alone. They trust behavior. If India wants to be seen as a democratic counterbalance to China, it must behave like one—transparently, respectfully, and consistently. Thank you!

Initiative

Connecting Sri Lanka to global development projects through futures research.

CONTACT

GET IN TOUCH

contact@millenniumprojectsrilanka.org

+94 714447447

© 2025. All rights reserved.